I'm calling a tie between Wanda and Davis -- Wanda for coming pretty close with the 8:30 a.m. Tuesday guess "The word Pyrex suggests that the subject is

glass; could it be a clock tower face? Something to do with a lens at Cal Tech

or PCC? Looks like the 1930s..."'

And Davis also wins for pretty much nailing it at 9:38 a.m. Tuesday guess "Looks like it could be a mirror for a telescope; Mt. Wilson, maybe?" followed five minutes later with "Too big (and too late) for Wilson; make it the Hale Telescope for Palomar."

This week's prize is lunch with yours truly, so Wanda, contact me next time you're in town; Davis, e-mail me at

annerdman.ladyofleisure@gmail.com and we'll make a date!

In the photo above, with throngs of people watching, a Pyrex telescope disc 200 inches in diameter, weighing 20 tons and made by the

Corning Glass Company, is offloaded from a rail car in

Lamanda Park on April 10, 1936, so it can be transported by truck to the optical lab at

Caltech.

Because the disc was so heavy and yet very delicate, the train trip from upstate New York to Pasadena took weeks at a top speed of 25 miles per hour.

The disc was greeted by a contingent that included

Edwin Hubble, the man on the far right in this group:

It was actually transported to Caltech by two trucks -- one pulling, one pushing:

At Caltech it would undergo more than a decade of painstaking grinding and polishing before being transported to its final destination: the

Palomar Observatory in north San Diego County.

Why did it take so long? Delays were caused during

World War II.

Led by

George Ellery Hale, the Palomar Observatory telescope project began in 1929 with a $6 million grant from the

Rockefeller Foundation. Hale had hoped engineers at

General Electric could create a disc from fused quartz. After unsuccessful attempts with GE, in 1932 Hale turned to scientists at Corning who believed their Pyrex

borosilicate glass could meet his requirements.

The Pyrex disc had only a rough, flat front surface. Here is a photo of men at the Corning Glass Works pouring molten Pyrex:

Pyrex does not expand or contract due to shifts in temperature, so Hale knew this would be a winner for Palomar Observatory, which sits atop

Palomar Mountain and experiences weather shifts ranging from snowy cold in winter to brutal heat in summer.

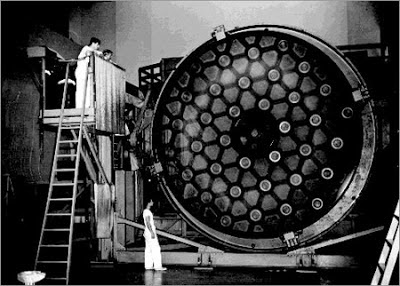

Here you can see a 102-inch grinding tool at Caltech smoothing the rough Pyrex surface:

And here is the finished product 13 years later -- the beautifully refined

telescope mirror, polished to an accuracy of two-millionths of an inch.

Over the years, the Hale Telescope at Palomar helped scientists verify dozens of theories, including the fact that quasars are extremely powerful yet distant objects, and that the universe is expanding, as Hubble had theorized.

Corning has a nice history of the project, including additional photos,

here.

The blog

Palomar Skies was started by the observatory's director of public affairs and ran until July when he left for another job.

Toward the end of lis life, George Ellery Hale is said to have looked up at the sky and rejoiced, “It is a beautiful day. The sun is shining and they are working on Palomar.” He would not live to see that telescope finished, but it was named for him.

It was the largest telescope in the world for nearly 45 years until 1993 when the

Subaru telescope, whose mirror was also made by Corning, was launched in Hawaii.

Many thanks to Caltech, which owns and operates the Palomar Observatory, and to Corning Glass Company.